Woody Allen, Cinema, and the Art of Wonder

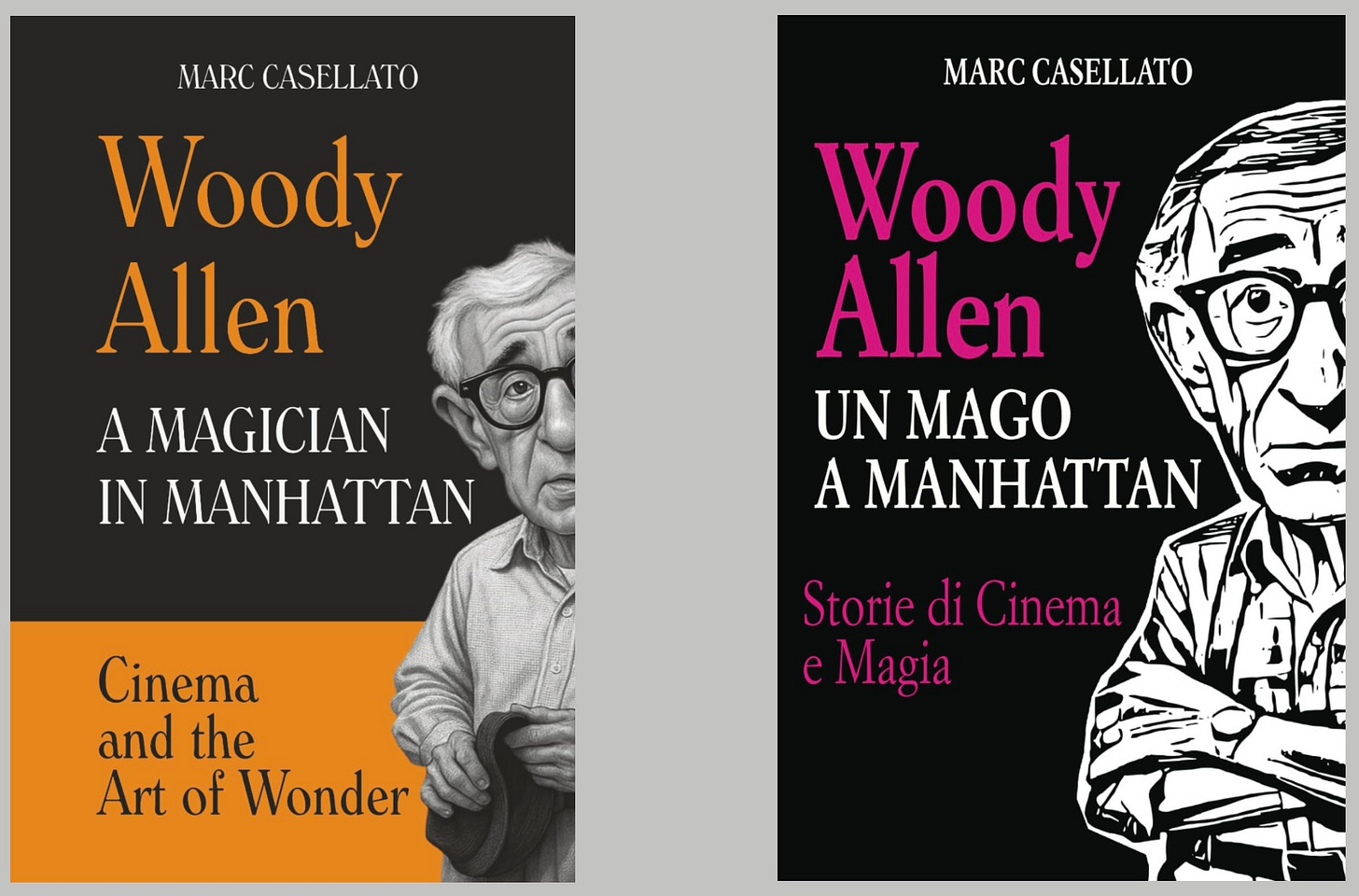

A review of Marc Casellato’s book on magic in the stories of Woody Allen (2025 English Edition)

My first exposure to the films of Woody Allen was Annie Hall (1977) which has been my favorite film since I was a teenager, catching it first on television at random—I think it was on the rooftop scene, where Woody Allen and Diane Keaton are discussing aesthetic criteria in an amusing dialogue juxtaposed with discordant but subtitled interiority. There are films one appreciates and then there are films that become critical reference points—lines in them taking on meaning and comfort in daily life, snippets of comedy to lighten loads and soften edges. That’s Annie Hall for me. The quips of Alvy Singer and the la-di-da of the eponymous character he falls in love with became keepsakes stored up for quick access in moments of either banality or grief.

I suppose the use I’ve made of Annie Hall constitutes a kind of magic in and of itself. Maybe that’s why the title of Marc Casellato’s book—Woody Allen: A Magician in Manhattan—clicked so resonantly in my brain. The book is premised on the fusion of magic and cinema that is so prevalent in Allen’s enormous body of work—in his prolific writings (numerous short stories and plays, and even one novel) as well as his filmography, where he has been director, screenwriter, and/or actor.

Casellato’s first exposure to Woody Allen was through the film Sleeper (1973). Another Allen/Keaton partnership, that film bends reality as science fiction—showing us an imagined and very distant future full of technological elements and special effects that allude to magic. What he recognized in Sleeper led to a stimulating journey, culminating in the writing of this book. Casellato—an Italian from Turin, who met the subject in March 1996 (and three more times after that)—describes an alliance of vision between himself and the filmmaker. It’s also a shared recognition of the trick of the trade, the sleight of the hand, and the measure of a craft that traces its inspiration from Bergman to Fellini.

Casellato tells the story from his own evolution as a boy enamored of the performance of magic to a sophisticate fully appreciative of Allen’s role in bridging the magical elements of illusion, imagination, and storytelling. He is a student par excellence of Allen’s entire body work. To give you a demonstration of his passion on this topic, I will quote from a conversation between us in a DM on Instagram:

“Woody Allen is often discussed as a filmmaker, writer, and jazz musician, but people rarely focus on the fact that, before he became ‘Woody Allen,’ he was drawn to magic and illusionism. I wanted to show readers how this interest is a constant presence throughout Allen’s work.”

He goes on to mention Allen’s subtle way of putting “Easter eggs” in his films. In the book, Casellato gives several examples of Allen’s use of the “Easter egg” device—a way for the filmmaker to subtly communicate meanings or even jokes. Such “Easter eggs” are often noticed by a niche community of fandom. Allen uses the “Easter egg” to display his passion for magical memorabilia. One “Easter egg” called out by Casellato in the book is a poster visible behind Diane Keaton in a scene in Manhattan Murder Mystery (1993). The poster is displayed as a centerfold in the book—an advertisement for A Night in Tokyo as created for a United Magicians troupe performance in the interwar period. Allen, fond of this treasure apparently, repurposed it as a prop in Melinda and Melinda (2004). One poster, two films, two eggs. Visual proof of a passion that runs deep.

“[R]eferences to illusionism are practically everywhere [in Allen’s work,] Casellato says. His creative process is underpinned by the illusionist’s mindset—what Casellato calls magical thinking, or how a magician turns what sees impossible into effect. Imagination plays a role. So does manipulation. Like a hall of mirrors at a theme park.

The magician’s trick of perception is everywhere in Allen’s works, as Casellato explains. To underscore this point in the book, he refers to a scene in Irrational Man (2015). Abe (Joaquin Phoenix) and Jill (Emma Stone) are distorted in the hall of mirrors—symbolic of the philosophical distortion of crime and punishment in the film’s plot. Abe deceives himself and Jill into questioning a Kantian or absolutist view of morality.

To ask whether murder is ever justified is what the moral philosopher does. To show you a mirror that alters your perception is what the magician does. They’re both challenging you to think differently. One is giving you a thought experiment. The other is more visual—a shake of a scarf, perhaps, to focus your attention, or a move by the magician to disguise his/her methods. Magic is not so much in the eye of the beholder as it is in the perception of the audience or the reasoning of the thinker.

I like Casellato’s thoroughness in showing the reader the history of magic performance and then tying Allen’s personal and professional narrative into that progression. As Casellato notes, magical performance is explicitly woven into Allen’s films, like Shadows and Fog (1991), where the circus is the main stage for the plot. And this film is descended from an earlier work of Allen’s—Death: A Comedy in One Act (1975). Thus, a decade and a half sees the evolution of a story that took root in Allen’s mind as a complex, darkly comedic script exploring moral questions about crime and innocence into a mesmerizing show of shadow, fog, and optical illusion that recalls early German Expressionism in cinema.

I wouldn’t have seen the link between German Expressionism, magical shows, and Allen’s work without Casellato’s book. Once seen, however, it reveals a clean throughline across the filmography. It’s not just smoke and mirrors—or is it?

I haven’t seen the film Stardust Memories (1980) so I was utterly awestruck by a centerfold image in Casellato’s book that shows Allen in that film appearing to levitate the actress Jessica Harper. It’s even mysterious the way Casellato recalls the scene. Allen’s character, Sandy, and Harper’s character, Daisy, are standing in a meadow. As Sandy levitates Daisy, “he passes a large metal hoop around her,” writes Casellato, “to prove there are no supports.” It is, indeed, presented as an act of levitation—the impossible rendered possible, and yet, as Casellato asserts, Daisy never rises. She’s merely suspended. The effect on the audience is further proof of Allen’s magical skills. It’s not the eye of the beholder that is bending reality. It’s the audience who are deceived into a belief that the impossible has occurred. Even I, someone who hasn’t seen the film, sense the wonder of the moment from the picture alone! This is Casellato’s work—his decision to use the photo and to blow it up across two pages in the book.

Casellato eloquently lays forth the methods of escaping unsatisfying reality seen throughout Allen’s works: outrageous fantasies, breaking the fourth wall, substance experimentation—the cocaine sneeze in Annie Hall, for instance, or Annie’s use of marijuana before sexual intercourse—and so on down the list of magical and supernatural techniques: levitation, teleportation, dematerialization, time travel, hypnotism, trances, divination, metamorphosis, ventriloquism, and enchanted screen doors between projection and audience. The book is a veritable academic textbook containing the histories of these types and uses of magic and Casellato skillfully shows us that in his entire career Allen has never neglected to use magical thinking and methods in telling stories and clarifying existential truths. Without recanting the book chapter by chapter, there are however a few things I would like to dwell on.

Casellato draws a parallel between Allen as a Luddite—still writing-typing on an Olympia SM-3 and completely inoculated from the temptation to use AI in his work—and the growing competition between traditional magical mediums and the ever expanding market of “deadbots” and “griefbots.” Even though Allen, as a writer, is safe from the looming threat of AI replacement—for, as Casellato puts it, “no algorithm replaces a writer’s imagination”—there is a danger which Allen foresaw as early as 1983 with Zelig. This movie was groundbreaking in many ways, notably in its prophetic themes as well as in the techniques deployed to make it. The eponymous character, Zelig, played by Allen himself, was a quick-changer—skilled in metamorphosis. He could transform his appearance at will, something he constantly did in order to avoid exclusion. He undergoes hypnosis by his psychiatrist (Mia Farrow)—a form of treatment that promises to actually cure him, but which is overtaken by damaging, unethical, and recklessly experimental methods that end up foreshadowing the problems we are negotiating in the present year. As Casellato asserts, the film Zelig feels like prophecy with its allusions to societal pressures of conformity, the erosion of individuality, mass consumerism, endemic transactional relations, and the manipulation of people by the media without transparency or distinction between truth and lies. Of course the paradox of magical illusion is that it’s both deceptive and revelatory, and in the age of AI, Casellato reminds us that the question is no longer, what is real, but rather, can we trust our own eyes? Illusions in the traditional sense required a skillful hand, but AI removes that agency and transparency from illusion. In some ways, it even removes consent.

I think it is also worth pointing out Casellato’s explanation of how Zelig was also technologically ahead of its time. Made ten years before the technology adopted by Robert Zemekis for Forrest Gump (1994), Allen used a complicated cinema graphic technique to place his title character inside historical footage. Zemekis had the Kodak cineon scanner to effect imagery that showed his title character thrust into the spotlight of the twentieth century’s key events. I think this is one of the most profound revelations in the book. This is the magic of technology, something that changes, and Allen has been a force who not only mastered its use but found innovative workarounds when it didn’t keep pace with his vision.

Pace is another thing I think it’s important to mention here. Technology is fast and it does change, and this is why it is so important to stop and notice when someone arduously makes a point to remind us that life is not supposed to be a race. One of the most beautiful movements in Casellato’s book is the one where he introduces the reader to Héctor René Lavandera, also known as René Lavand (1928-2015). This poet of stillness, whom Casellato had the honor of meeting, “transmuted limitation into style.” (Casellato, p.200.) From the age of seven, he was one-handed, and so, as someone who wanted to do card tricks, he invented card magic for one hand. He was “a poet of close-up: stories woven around silences, impossibilities shaped at walking pace.” The point was to slow down the tempo, notice the stillness, and hear the cards speak. Casellato compares Lavand’s “voice to cards” method with Allen lending “voices to the anxious, the romantic, the foolish, the brave.” (Casellato, p.201.) Lavand slowed magic down to a pace that could perceive presence itself. Allen has given voice to what is otherwise intangible or abstract. These two ‘voice’ methods, Casellato asserts, are but another kind of ventriloquism—the art of giving voice to the inanimate, and seen across Allen’s work, from Take the Money & Run (1969), Broadway Danny Rose (1984), and Radio Days (1987).

Woody Allen is a nonagenarian now. He just turned 90 last year, and yet he is not retired. Neither from filmmaking nor writing, nor from, presumably, the art of magic. He wrote and directed a French film, Coup de Chance, in 2023 and did voice narration for Mr. Ficher’s Chair (2025). He also published his memoir in 2020 and published a novel—What’s With Baum?—in 2025. There are reports of another film in the works this year, reportedly in production in Spain. It is important to note where Allen stands in life now, what he is doing, because it means that he has now been making films for just under six decades and he has been writing (jokes, plays, short stories, novels) since he was in high school. At the age of seventeen, he became Woody Allen—a name he took to disguise himself from his classmates. All this is proof of something rare—a career with influence, longevity, and impact across generations. It’s not just that he’s famous or even that he can tell a coherent story with a start, middle, and finish. It’s that in the course of his gigantic career, without being pedantic or predictable, he didn’t just insert himself in the chronology. Nor did he simply do the work as he learned from others. That’s like saying that Harry Houdini is just a figure in the history of magic, when, in fact, he is a vector of its trajectory. Allen mastered the craft and the wonder of cinema—and became a master of it.

Casellato’s book may not be the entire story, but it must be a decent proportion of it, since it looks at Allen’s life and names those elements which have always been there—the tricks, the stories, the jokes, and underscoring all of it, the curve of moral and intellectual reflection, of human imperfection, and of life’s ambiguities. A powerful throughline through all of it—both Allen’s life and work, and Casellato’s book—is the core idea that magic is paradoxical. It’s both deception and revelation; it’s also both performative and sincere when elevated to its highest art form. It can provide us with escape hatches that make life bearable, but it also holds the potential to bring us in alignment with the only thing that exists—presence. Casellato is passionate on the subject and it shows. In the end, he implores us to connect with magic’s most endearing gift—astonishment, surprise, enchantment. These things are so dazzling because they bring us back to something that some of us lose touch with after childhood. Casellato holds onto that special thing by reminding himself to forget. When we forget, life becomes mysterious and wonderful again. That is, after all, what makes life not only bearable, but sometimes beautiful.